I am trying to make sense of things, which is why I find myself ruminating. Chewing like a cow on my thoughts. Cows also ruminate. Differently though. After ingesting lots of grass, cows find a place to lie down to more thoroughly chew their food. This process of swallowing, “un-swallowing”, re-chewing, and re-swallowing is called rumination, or more commonly, “chewing the cud.” Perhaps my mental cud chewing is some undiagnosed shit, as I have more than once been called a bull shitter. Maybe it’s some spiritual shit, as I have more than once been called a heifer.

During my ruminations, a thought from years ago or months ago or minutes ago, a sneaky motherfucking thought can get caught in an endless cycle that moves through my mind, down into my gut, up into my heart, and back into my head all day for days. This week’s rumination was on Bill Gates. When news first dropped of his divorce with Melinda French Gates, I couldn’t understand why a couple married that long would divorce. Just didn’t make sense to me in my naivety about relationships and such. But then I read he’d been a serial philanderer, and maybe something worse, for years. This took me back to my ongoing thoughts about John Tubman. I wonder what it felt like for Harriett to love a lover who betrayed her and still not be able to get him out of the rotation of her habitual thinking—looking for nutrients that were perhaps never there.

And that just sits me down in the grass with my questions, not about Bill or John or Harriett, but about humans, about humanity, about the cows. Is there a goal for reckoning with the atrocities done to the folks on this land, or is everyone just chewing cud, full of it. What would it take for folks to trust each other enough to confront history healthily on a massive scale? Is that ever going to happen or is it not even what people want? Are we out to pasture and don’t even know it? Being led to some ultimate slaughter because we’ve never stopped chewing long enough to digest what has happened here. To extract the lessons, expel the shit, and not lap it up again and again for no reason, no reason at all on repeat. How do we repair the harm of slavery, Jim Crow, and lynching? I grind these questions through my teeth, down into my gut, throw them up, lick them down, throw them up again, sleep with them on my stomach, wake up with them on my face.

I wonder if I, who unlike cows that ruminate out of necessity, am doing so as a trauma response? Am I eternally grazing? Do I get to have memories of my dad’s size 11 hooves stomping my mother’s face in my mind forever, forever ever? Oh, the amount of intrusive reviewing and revisiting and revising that I put myself through after a speech or a panel discussion or after I’ve met someone whose thoughts make me think twice. Always wanting to rewind the time, to break things down just a little bit more, just a little bit longer. I can lie paralyzed by thoughts of a single color, a silly word, or a fumbled phrase. Is this something that will eventually go away? Do I want it to? I think the older I get, it only happens more.

I ruminate over people too. I sit and think and think and think about Kanye or my Ex or my future love or my future Ex lover and wonder if they are ok and if there is anything I could do to help them or to help the people in my life who are like them? I even think about how their brains work and wonder whether they ruminate too? Do they reflect on circumstances in ways that require large swaths of energy—relive moments of emotional unrest or emotional bliss while waving their tails under the summer’s hot sun? Do questions about Malcolm and Mariama and Mumia know no end in their minds like mine? Do they get so lost in their thoughts that they see someone talking but cannot make out the words they’ve said with lips just flapping from side to side in the wind?

This Erykah Badu on and on and on-ism is also something I do with history. Sit myself in the haul of a ship tightly packed with piss and vomit and blood and death at my feet and at my head. I am Antoinette Sithole running beside a dying boy through Soweto. I am Winnie Mandela 491 days solitarily confined. I, too, chew with the ancient aurochs and swim with the ship jumpers.

Someone told me to practice writing the ruminations out. Not a therapist, just a fellow ruminator who reported to have found a way to reuse their unmanaged, unmitigated written ruminations to reimagine. To release them like an unruly herd. I want to reimagine what the American version of the Truth and Reconciliation Trials would look like? A social epic I suppose. Can we stand to memorize other people’s lines? Like future replay in reverse.

Rumination was originally defined as repetitive thinking about negative effects and their possible causes and consequences. But rumination can also be beneficial when it focuses on reckoning with an error—one’s own and those of others. Like spending hours thinking about what healing feels like in our bodies, in our minds. Rumination is also helpful for goal attainment rehearsing a task—seeing ourselves, smelling ourselves, in a future as we wish to see it. When was the last time you ruminated on a world repaired? A people healed? Remembering that finding social nutrients is an all-day job and gave yourself the whole day to do it. Write out your regurgitations, prepare for reconciliations that repair the harm because we can ruminate on the problems until the cows come home, but how much more can our minds really take and who is it actually feeding?

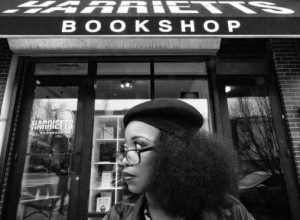

For the last 10 years, Jeannine Cook has worked as a trusted writer for several startups, corporations, non-profits, and influencers. In addition to a holding a master’s degree from The University of the Arts, Jeannine is a Leeway Art & Transformation Grantee and a winner of the South Philly Review Difference Maker Award. Jeannine’s work has been recognized by several news outlets including Vogue Magazine, INC, MSNBC, The Strategist, and the Washington Post. She recently returned from Nairobi, Kenya facilitating social justice creative writing with youth from 15 countries around the world. She writes about the complex intersections of motherhood, activism, and community. Her pieces are featured in several publications including the Philadelphia Inquirer, Root Quarterly, Printworks, and midnight & indigo. She is the proud new owner of Harriett’s Bookshop in the Fishtown section of Philadelphia.