On a winding road this side of South Mountain

which looms beside the less and less quiet valley,

we park the Jeep just past a roadside spring

that streams from a pipe fastened to a rock.

Such an insufficient description, I know,

but you don’t need to see it, just trust

that today as we lift empty plastic jugs from the back

and pop the caps to fill up on the free spring,

I’m stuck in time, or maybe just seemingly so

because nothing passes—not a car, a bike, or a breeze,

not a sound from the songbird likely stuck somewhere

deep in the somewhere trees erectly still on the mountain.

I’m bound by the thought of us here, somewhere

in the muck of life and all that’s falling

each day—each leaf, each dripping drop, each glimpse

of sunlight reflecting from the cascade of uncertain endings.

Someday I’ll ask where this went, where it fell or what it

fell into. But if I stay here, stuck, just one moment more,

I know I’ll find a way to slip this into my pocket,

zip us up, cap these jugs, preserve the roadside spring

that begs us to drink—drink from this leaky mountain,

as if we seek the answers or even know how to ask.

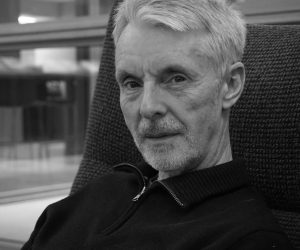

Wes Ward was born in Dover, Delaware, though roots tie him back to Chester County, Pennsylvania, where his dad was raised. Now a familiar stranger to Philadelphia, Wes lives a couple hours due West of Independence Hall and teaches high school English and college writing. He earned his Master’s of Arts in Writing from Johns Hopkins University.